Why do it?

One of the main ways that we manage the huge amount of information surrounding us is by categorising things. It is literally built into our brains, it is the fundamental way we think, dominating how we perceive the world.

Firstly it cuts down on the amount of information that we need to process. If I’m driving, I can only worry about the top four or five threats at any one time. I categorise stuff that I can see into

- Things that might do something I wasn’t expecting, and

- Things I’m going to assume are inert and no threat.

If I drive past a parked car, I don’t need to worry about if he has seen me or what his next move is likely to be. I just need to drive around him, able to concentrate on the moving car in front of me that might do any number of strange things, or other things that might be a threat. It’s quite an adrenaline rush when the parked car pulls out without indicating (which happened two days ago, incidentally).

Secondly we need to categorise things to be able to infer rules and predict events which we do more easily with categories than individual items. Stinging nettles have serrated leaves; so if I see something with leaves like that when doing the gardening, I put on gloves. There are plants that look a bit like them that don’t sting, sneaking behind the true stinging nettle’s defence mechanism. I wear gloves then as well; they are not that inconvenient and it avoids making a mistake and getting stung.

Categorisation is also a way, possibly the only way, of forcing order on to a disordered world. In the middle of the eighteenth century, Carl Linnaeus invented a binary nomenclature for plants, giving each a two word name. The first is the broadest of the groups and the second the more specific name. This has been extended to most if not all living things, thus we are Homo sapiens (wise man), not to be confused with Homo habilis, Homo erectus and so forth. This has grown into an entire science, taxonomy1, which flourishes to this day. “All” he did was to put things into categories, yet it was undoubtedly a major step forwards in the study of living things.

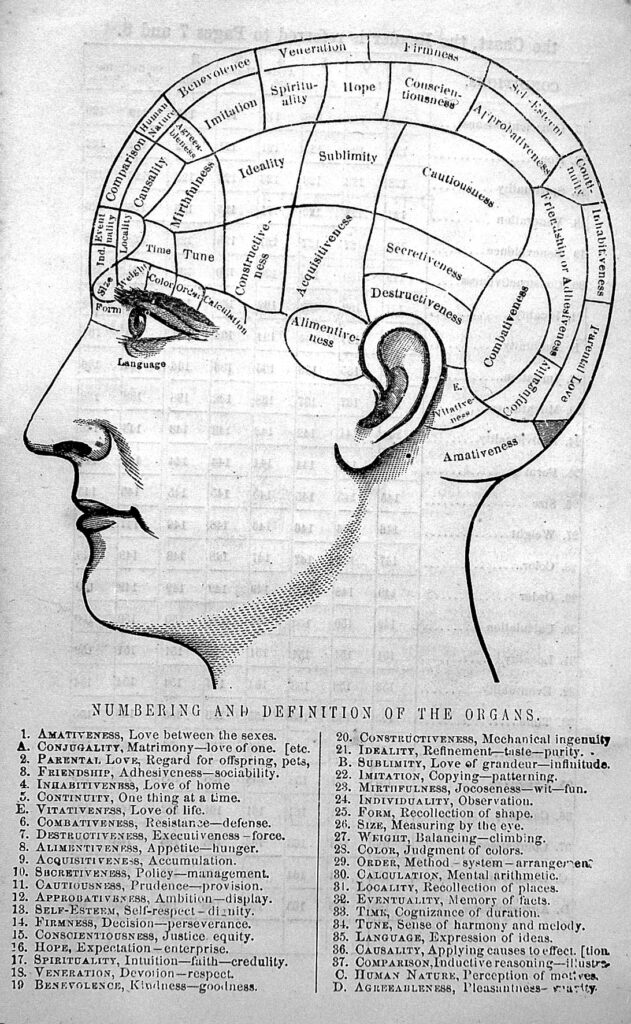

There’s physical evidence for categorisation being literally built into our brains. By studying medical cases where part of the brain has been damaged, usually by strokes (where part of the brain dies from blood failing to reach it) or by occasional and rather gruesome accidents, we are able to see how different areas of the brain store different things. For example after a stroke, one guy could remember the names of anything that was normally found outside a house such as a tree or a mountain, but not anything that is normally found indoors such as a teapot or an armchair. His brain had clearly stored them in physically different places. Of course, that’s just one guy but it demonstrates quite how fundamental categorisation is. The fact that where memories are stored varies from person to person also demonstrates that evolved systems, like the brain, are stupidly complex. Victorian phrenology was always an idealisation (and why did the bits of the brain away from the surface do nothing?)

Categories matter a lot, even from childhood. A friend of mine from university went on to teach biology to primary school children including, of course, tadpoles. Between egg and frog they go through developmental stages – I confess I forget them – but it’s to do with growing legs and the like. When asked if this particular tadpole was stage 3 or 4, she said that it was rather between the two. But to her class, this answer was outrageously unsatisfactory – they wanted to know, definitely, which category was this poor creature in. As you can see from the figure below, it’s a continuous process.

My elder son, aged about three, once saw something he didn’t understand (a nun, actually). We tried to explain it to him but he was too young. He looked puzzled for a bit, pointed to a tree and a flower and said “that’s big and that’s small”, retreating into comfortable categories that he understood.

Problems with categorisation

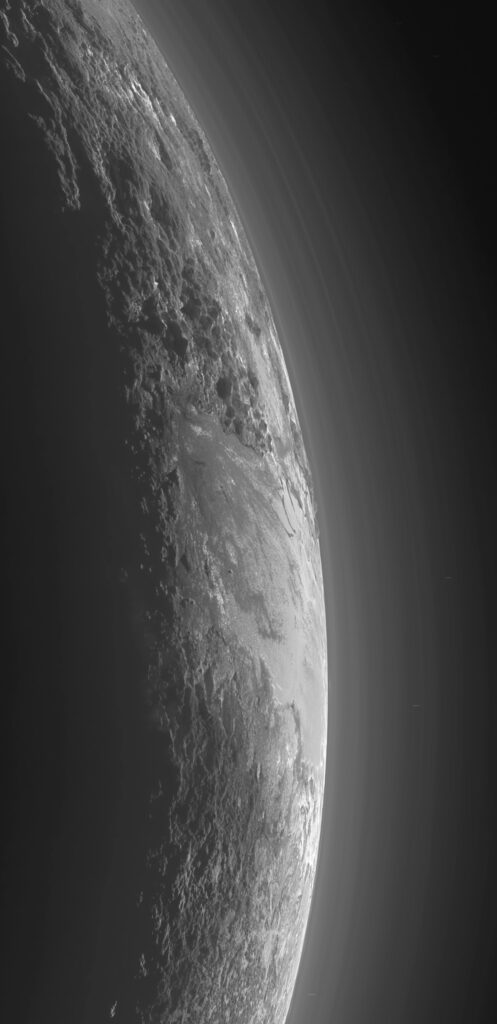

No matter how useful and necessary they are, there are significant issues with categorising things. The first is that you add structure that isn’t really there. From 1930 Pluto was unknown, then it got discovered and was a planet until August 2006 when it got demoted to dwarf planet. A lot of people got very upset by this, but Pluto and anyone living on it really doesn’t care, only we care about its demotion. Similarly the tadpoles from the primary school don’t care if they are stage 2 or 3, but apparently we do, even as children. The real advance with Pluto, from not even knowing it was there until 1930 through to the highly detailed photographs (below, from the New Horizons mission) created less of a stir in the popular press.

Adding structure like this can give issues because it can be so arbitrary. For example, there are all sorts of age limits – drinking, driving, criminal responsibility, voting, having sex and so forth. Why can a 16 year old teenager join the army, pay tax and possibly give up his life for Queen and country, but not be able to vote? Fundamentally it’s inconsistencies between the category boundaries that were added by different people at different times.

What is the age of criminal responsibility? In the UK the limit is 10 years but it varies a lot throughout the world. At what age should a young criminal lose the right to anonymity because they are so young? I think it’s 18, but we end up with the absurd position that some murderers who knew exactly what they were doing have their identity protected because of their age. One size does not fit all.

Abortion

Lastly what I think is the most difficult subject of all, abortion. A baby develops in a continuous manner from a fertilised egg at the start to a fully fledged human at the other – where do you put the limit? A couple of friends of mine (American catholics) are very clear on this, life begins at conception. Another American with whom I had a rather unsatisfactory argument was also pretty clear, a woman’s right to choose, right up to birth. I honestly don’t know what I think on this. At conception it’s not a human – potential and actual are different, unquestionably a woman’s right to choose. At the other end of the pregnancy it’s a separate human able to survive on its own; I don’t see much difference between a day before birth or a day after. In the UK the abortion limit is is based on whether the baby is viable outside of the womb. I suppose that this is as good an attempt at making the limit less arbitrary, but it feels really artificial. Possibly when it can feel pain or when it has self awareness would be less arbitrary, but since we cannot know these things with current technology, they are not very helpful.

I realise that arguments about abortion are much more than about categories. I listened to a radio programme about past debates, and one of the anti-abortionists was mourning the children that were never born. I was a little shaken by this – I have never regarded early terminated foetuses as children, she did.

Category edges

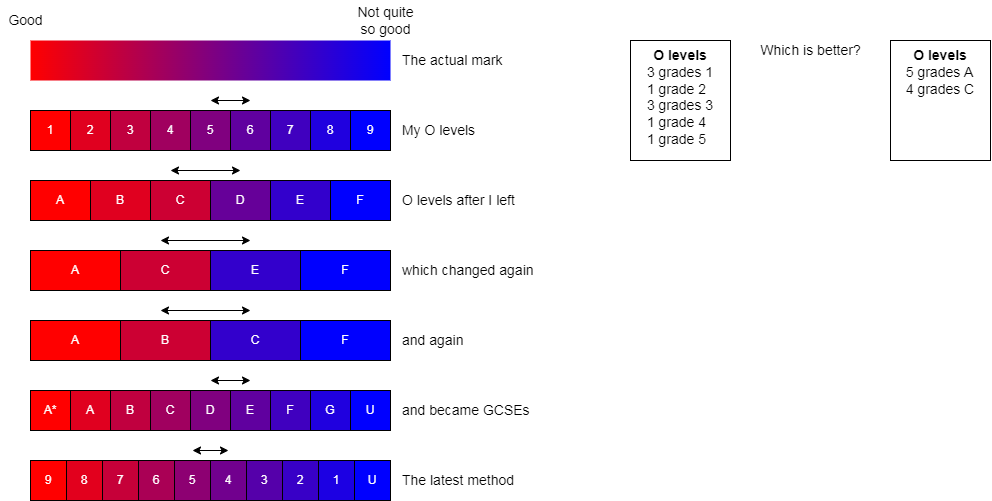

A second problem is that you get issues with at the edges of the categories. When I took my O-levels (now GCSEs) a decade or five ago, the grading was 1 (best) to 9 (worst). 1 – 6 was a pass, 7 – 9 a fail. That seemed to work OK as a marking scheme but of course it had to be ‘improved’. It was ‘improved’ many times to the point that it was difficult to compare grades. Firstly it went to letters (A-F), but more importantly, fewer categories. Then to A, C, E and F which got renamed to ABCF. And now, of course, they’ve turned the numbering system upside down so one is the lowest and nine the highest. So we have a bunch of different categories which cannot be compared. So, we don’t show the original mark, and we cannot compare exam results from different years.

Meanwhile in the US, SAT scores are scored from 400 to 1600. So why not use the mark all the time and do away with grades? “Because it’s unfair, one person who is similar to another will get the same grade, but a difference of a point or two should not change your grade.” True, o wife, but not if you are at the edge of a band where a point can demote you from an A grade to a C. The arrows in the diagram show how much a single point can shift you if you are close enough to a boundary. The fewer the categories, the more we iron out the differences within them and the more you pay for this if you are close to an edge. Better to display the mark and people can learn that it’s a spectrum, that 1% doesn’t matter and nobody gets penalised for being on the edge. By the way, I have no idea where the actual grade boundaries were, I’m making them equal because I don’t know better. And yes, my degree was a 2:1, less than 1% away from a first.

Throwing data away

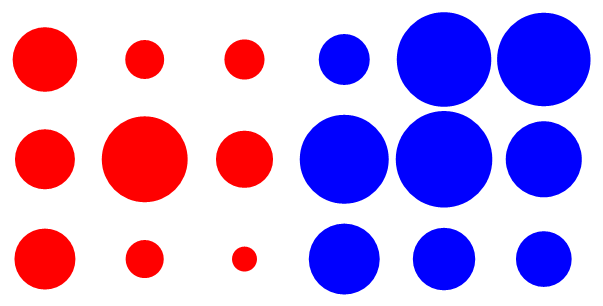

As well as adding information that we’ve invented, categorisation, like any summarising technique, throws data away. I am an engineer, working with my customer on an algorithm to detect differences between peaks and troughs with noisy data. His first approach was “divide the data into bins”; I knew instantly that that was a bad idea because of all of the above, and felt suitably smug when the final, much better algorithm didn’t throw anything away. Similarly, categorisation also emphasises the differences between categories, and plays down the variation within one. (All these effects are quite closely related but can show themselves separately, so I’m describing each.) Consider the following diagram of smaller red circles and bigger blue ones.

It is clear that there is some overlap in sizes, but it is surprising how much overlap there is. The distributions of the radii are shown here4; the red circles’ radii are randomly picked from 0 to 75%, the blues from 25% to 100%. If you wanted a large circle, you’d undoubtedly want to go to the blue store.

A corollary to wanting to think in categories is that there can be significant upset, or “cognitive dissonance” when something changes category. It can be joyous as you rethink your world, but by the same token it can be unsettling, making you question a lot of assumptions with which you were previously happy. There is the wonderful example from Richard Leakey, who, on finding chimpanzees using tools, famously declared “Now we must redefine ‘tool’, redefine ‘man’, or accept chimpanzees as humans.” Erasmus, on reading Cicero, remarked “A heathen wrote this to a heathen, and yet his moral principles have justice, sanctity, sincerity, truth, fidelity to nature; nothing false or careless is in them”. Not so heathen then². Or if you think that is too intellectually pretentious, consider “I believe that a stranger is just a friend who I haven’t met yet”. Saccharine as it is, it’s all about things, people in this case, moving between categories.

The category is the thing

In recalling information, we don’t think about the individuals but only their categories because we don’t have time for anything better (or more precisely, evolution hasn’t needed to upgrade the brain to do so because this way works well enough). Most of the time thinking only about the category is pretty reasonable as well – if you’ve seen a bear attack a human then it’s a pretty good idea to avoid all bears. Perhaps you are not being very fair on other bears that might just want their bellies rubbed, but it’s safer to assume that they are all dangerous. However recalling the category and ignoring the underlying individuals or continuum is problematic.

Mammals are defined by feeding their young with milk. The overwhelming majority also give birth to live young and don’t have beaks. When a pelt and a sketch of the duck billed platypus was first sent back to England, it was thought to be a forgery because mammals don’t have beaks; disbelief greeted the idea that it laid eggs. One group of people had known what they were for generations (and also that they were poisonous, another thing that mammals usually aren’t), but because these people were in the category “aborigine”, little notice was taken of this. Female duck billed platypuses don’t even have teats to produce milk, they sort of sweat the milk from specific parts of the body. When its genome was sequenced4 there was a good mixture of mammalian, reptilian and unique genomes.

Generalisations

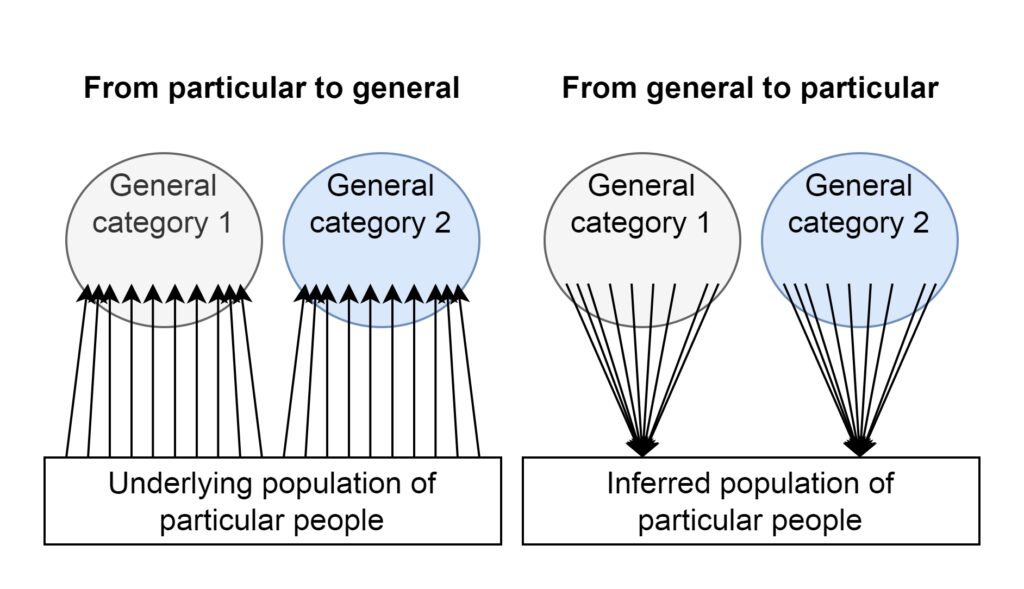

Going from the particular to the general is usually OK. If you are doing a test for the efficacy of a drug, you put those who had the drug in one group and those who did not in the placebo group. There is going to be a bunch of confounding variables5, but if the sample size is large enough and you’ve designed your experiment well enough, you may be able to tell if the drug actually worked. If you want to determine the pay gap between men and women, then tally up the salaries of men and women separately and then compare. If you want to determine the pay gap between men and women doing the same job, same idea but you need more categories. You are not changing data or making assumptions.

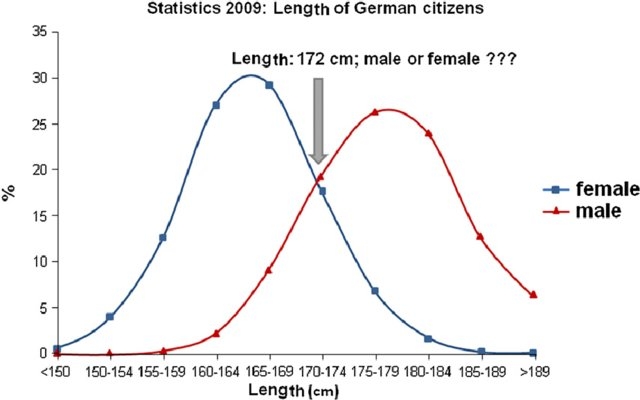

But we have a tendency to go from the general to the particular, or more exactly think that a member of a category is going to have the average characteristics of that category. This must be resisted. A simple example – for a long time the army would not permit women to be gunners because they were not strong enough. Strength is, I imagine, important for a gunner, having to heave heavy shells around, but not all men are strong enough and of course a few women are. We go from the general “men are stronger than women” which is true on the whole, and “we need strong people for gunners” (which is also true) and end up with “you are a woman and therefore cannot be a gunner” which is prejudice – judging too early, or as one judge was once accused, of “premature adjudication”. I don’t have graphs for strength, but here’s one for height, or possibly length, of German citizens. There are, as you see, plenty of women taller than men and no doubt stronger as well. Permission to be a gunner is now done on the basis of that person’s strength, independent of gender. So simple and in retrospect, so obvious.

Prejudice

Our love of categorisation makes us really good at this. The previous example can be summed up as “women aren’t strong enough to be gunners” which might be true on average, but it’s rough on strong women who want to be gunners. When I grew up (in the sixties and seventies) it was commonly understood that women were not as good at driving as men. Although I have no evidence to support this I expect that on average it was probably true. To my shame it took a highly intelligent mechanical engineer (who could drive – at the time I could not), to point out that this was true simply because the men got more practice – the husband would drive to work every day and so would do the majority of driving if husband and wife were going out together.

Probably the worst is colour prejudice simply because skin colour is so visible. We distrust ‘others’, and black and white skins are so obviously different that it’s really easy to be prejudiced. I don’t know where this distrust comes from – small children don’t have it but older ones do. Is it taught? Is it genetically programmed and only occurs around the age of 5? I honestly don’t know.

All of my grandparents lived in Southall, some of my childhood was spent there in the sixties. This was the era of “whites only” in pubs and I think effectively a complete segregation between the two colours. I remember walking down the street with my aunt one evening passing two perfectly peaceable gentlemen with dark skin6 and turbans. They were talking in what was probably Punjabi but to our ears total gibberish. Bear in mind that this was the era before package holidays and anyone speaking French was viewed as a bit odd and untrustworthy; the second world war was within most people’s memory. To my retrospective shame we both burst out laughing; of course it was wrong, particularly by today’s standards and I’m not defending it, but it was a natural reaction to something that was very alien and therefore a bit scary. Being natural does not make it right in the sense of promoting a harmonious society, but it is foolish to pretend that the natural urge is not there – it leads to stuff like the National Front.

In a minor way I’ve just about been on the receiving end of it too, travelling through Sumatra in the late seventies. I had a beard, rather long hair and looked distinctly odd to native eyes. I fell asleep on a log waiting for a ferry and woke up to find a circle of around 20 faces peering at me, utterly fascinated; they all scattered as I awoke. I hate to think what caused it, but whenever we’d walk past children, their mothers would desperately snatch their kids away to safety, real fear showing in their eyes. I’m not trying to compare this against the prejudice that some groups get in the western world, or in any way to justify such, but it’s a universal and natural phenomenon based on seeing a category of people (“foreigners”) and not the people themselves.

Deliberately manipulating our tendancy for prejudice has a long and shameful history. How an army is taught to regard its enemy, Catholics and Protestants, the Japanese and the Chinese in Nanking, Germany and the Jews in the second world war and probably right now the Russians and the Ukrainians. It’s easy to teach that a group of people is sub-human, and when you’ve done that, it’s easy to kill them.

Categorisation is not unique

Different people categorise the world in different ways. Sometimes it’s trivial – English speakers categorise streams and rivers based on their size, the French by what they flow in to7. Sometimes it’s not so trivial – friends and enemies, one of us or an outsider and more recently, man or woman. Trans women base gender on what they feel themselves to be, many others base it on physical attributes, e.g. J. K. Rowling’s famous “people who menstruate”. The really daft thing is assuming that there is just the one way to categorise.

A couple of guys I used to work with are now trans-women, have changed their names and wear flowery dresses, good for them, I’m happy to call them women. One of them is a serious bowls player, won a women’s championship and got taken to court. The court ruled that there was no physical advantage from having extra muscle mass etc. in bowls and the result should stand, quite correct. But the swimmer who used to be on the men’s swim team switching to the women’s the year after clearly has an unfair advantage. Women may have less testosterone in their blood but men’s superior physique comes from more than just that. Arguing that by lowering someone’s testosterone level means that you are competing equally with cis women is a logical fallacy akin to getting cows to start up to stop it raining8 (and seems to be falling out of fashion), besides this is nature we are talking about so of course it’s a lot more complex than just one hormone9. This leads to the unanswerable question of “can a woman ever have a penis?”. It’s unanswerable because it depends so much on how the answer is going to be used, or to put it another way, “who is asking”? We need to be clear on the reason for using the categorisation. “Can I compete as a woman” would be yes for bowls and no for swimming. There are some cases not so easily solved – changing rooms, bathrooms etc., but we need to understand that it is the individual questions that are important, and the fallacy of the immutable concept ‘woman’.

Dualism

This is my favourite bête noire, explaining everything by assigning it to one of just two categories. Good things come from god, bad things from the devil. Selfish and selfless thoughts come from your id and your ego respectively. And for the more sophisticated thinkers of this ilk, something that’s trying to be good but doesn’t work out came from god and was corrupted by the devil. It’s an extreme example of categorisation, and feels as if we are advancing our understanding (and of course, sometimes we are). Sometimes this gets turned into a false dilemma – are you for us or against us? – to which the best answer is usually ‘no’.

Another interesting example of dualism is wave and particles in physics. Up until the early 20th century, waves were waves and could form interference patterns, and particles were particles that could collide with each other like billiard balls. Then it turned out that waves could act like particles and vice versa. Great confusion and description of wave / particle duality. The root problem is that photons, electrons or anything else for that matter are their own thing and behave a long way from day to day experience; what really upsets us is that the categories that we brought to the table don’t fit.

Another trap of dualism is in thinking that there are only two categories. A mathematical statement is either true or false, obviously, only actually that’s not true. Some statements can be proved false, some can be proved true and some cannot be proved to be either (this is Gödel’s theorem). Blair’s “third way” was a brilliant exploitation of this. Don’t get me wrong, it was complete, meaningless bullshit, but coming in and saying “hey, guys” and proposing a third way when the first two both had their problems appealed to the idea that there was a different, and therefore better, way of tackling a problem; pure genius, a shame that that is all he was good at.

Identity

Ignoring differences within a category also happens when you are within the category, perhaps particularly so as we enter the world of identity. Everyone seeks the security of a crowd of like-minded others so we all want to identify with a group. The trouble is that we are all very different and because we identify with a group does not mean that we are the same as a ‘typical’ member of that group. One guy I know once declared that “I’m sensitive because I’m gay”. Gay he might be and he is a nice enough guy with many positive qualities, but sensitivity really isn’t one of them.

Identity is a potent political tool. It’s easy to shout “God bless America”, “God is Great” and so forth without being too specific as to what you mean. As communications improved, so that became more difficult, and groups which had previously been separated, when meeting each other, could find themselves out of sync. There’s a story, probably apocryphal, that some lesbian co-operative from Camden went north to support the miners’ strike. There was an altercation between one of the mining community and a lady from Camden in which the latter was outraged at the former who was looking slightly bewildered, saying “well of course I pinched it, it were a nice arse”. (I hope that would not happen today.)

Once we were in New York, a little bit lost and standing on the street corner consulting a map. A guy came up to us and asked if he could help. Twenty minutes later we were eating the best hamburger’s I’ve ever had in his (and his wife’s) flat. He told us that America is like an elephant surrounded by blind men; one could feel the trunk, one the legs, one the tusks and so forth but it was just different aspects of a single animal. Even then it struck me that there was no guarantee that the animal existed. The more that the blind men met each other, the more arguments there would be on the true nature of an elephant, or indeed its very existence.

Now we seem to have left common sense behind. You have to be black to play a black part on stage because otherwise you won’t understand the “black experience”, as if there is just the one such, regardless of, say, parental wealth (and also implying that writers cannot write and actors cannot act). It’s also wrong for a straight actor to play a gay person on stage. Germaine Greer said that only if you were brought up as a girl can you understand what it is to be a woman. Much as I revere Dr. Greer as a real pioneer, the assumption that there is a single black / female / gay / transgender / whatever experience is both ridiculous and insulting because it assumes no diversity within the category and is pandering to Figure 10. But, the category is the thing. Billy Connolly and I are both white aged men but where is our shared experience? He was abused as a child and I was not. He’s funny and I am not. He grew up in a city dominated by Catholics and Protestants and I did not. He can weld, I cannot. We both have an appreciation for big engineering projects, but that’s also shared by my colleague Grant who is a South African black guy who, if you ask, is Xhosa, but mostly he’s just a really easy going dude called Grant. If you want to assign a common experience, “making things” would be closest.

And now we have the whole idea of identity, often based around skin colour or sexual orientation, going nuts. When I was a lad, not being colour prejudiced meant that you didn’t care about skin colour, now it seems to be one of the most important criteria for a job. I get the point about positive discrimination, but if you promote or employ someone based on their skin colour when they are not up to the job, it’s going to lead to yet more prejudice. It was like this for academic outsiders. Sophie Germain was one of the top mathematicians in France but had trouble getting started because she was not allowed to attend university lectures. Probably the best mathematician we know of was a clerk on the Indian railways. His problems in getting recognised were several, but one of them was because he had had little formal training and quite a lot of what he wrote was unintelligible and quite often wrong. Read this carefully – I’m not implying that skin colour, gender or anything else has anything to do with ability, and even if it did, as with the female gunners it should not matter. The real problem that needs solving is inequality of opportunity from birth which is much more difficult to fix (and does not generate good headlines). Free university education would be a step forwards and who took that away? To give him his proper title, that will be the war criminal Blair. I renounce him and all his works.

Finally

If you don’t believe that we like categories, why is the following (from today’s Telegraph) such good click-bait?

Footnotes

[1] For a gentle introduction, see faunafacts.com/classification-of-living-things/

[2] I’m being unfair to Erasmus here, but it makes the point eloquently.

[3] I confess to using a trick beloved of adverts and news programmes. The radii are indeed drawn from a rectangular distribution, but the circles’ areas which you perceive emphasise larger radii.

[4] nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/duck-billed-platypus-genome-sequence-published

[5] https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/2018/10/01/a-beginners-guide-to-confounding/, or Wikipedia for something more advanced.

[6] Well darker than ours.

[7] Un fleuve is a large river which flows directly into the sea. Une rivière is a river which flows in a fleuve or another rivière.

[8] Cows are supposed to lie down when it is going to rain. Therefore “kicking them to make them stand up is going to stop it raining”. It is surprising how often this false causal logic gets used without anyone noticing.

[9] https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/4-myths-about-testosterone/

Figure 1: https://www.chipsaway.co.uk/blog/how-to-stop-someone-parking-in-front-of-your-house/

Figure 2: Own work

Figure 3: L0022607 Phrenological chart Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images [email protected] http://wellcomeimages.org Phrenological chart, ‘numbering and definition of the organs’ New illustrated self-instructor in phrenology and physiology… O.S. Fowler Published: 1859 Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Figure 4: https://timhuntphotography.co.uk/5sg17qmavamgxqqpczks9vbywhcj08

Figure 5: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pluto_in_True_Color_-_High-Res.jpg (public domain)

Figure 6: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pluto_crescent.jpg#filelinks (public domain)

Figure 7: Own work

Figure 8: Own work

Figure 9: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Platypus_(Ornithorhynchus_anatinus)._First_Description_1799.jpg

Author: Frederick Nodder

Figure 10: Own work

Figure 11: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/50866680_Physiologic_Parameters_as_Biomarkers_What_Can_We_Learn_from_Physiologic_Variables_and_Variation/figures

Figure 12: Guardian 2018

Figure 13: Own work

Figure 14: The Daily Telegraph 25.05.22 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education-and-careers/2022/05/25/six-new-types-office-worker-one-do-sit-next/